In 1982, Catherine Linehan lost five of her children in a house fire. In took 40 years, and the persistence of her daughter, but that story is now being told

By: Russell Bowers

It’s a family tragedy many would find too much to bear. In June of 1982, a house fire raged through the Linehan home in the small community of North Harbour, St. Marys Bay. It was Catherine Linehan’s family in peril and when she sensed the heat from the impending flames, she shouted out to her two oldest boys.

“Francis, Neil! Get up! Everyone get up. The house is on fire!” Before long, she described how “everything was on fire: the floor, the walls, the ceiling.” The mother of 10 perched on a windowsill and through the open window, saw rocks waiting for her, some 15 feet below.

“I had no idea at this time where anyone was nor who needed rescuing.”

And she jumped. When Catherine regained her footing, she scrambled to account for her family. She shouted out for her husband, Eddy and their children. Once the flames were quelled, Catherine Linehan had to face the reality that five of her children perished. Francis. Richard. Sharon. Harold. Barry.

Ida, one of the five children who survived the ordeal, watched over the decades as her mother never seemed to grieve the deaths of her children, not outwardly, by any rate. Decades later, Ida visited the graves of her siblings with her own daughter, and upon seeing the headstones, her daughter remarked, “We know nothing about them.”

“It took me 27 years,” Ida now admits, “but I said, ‘Mom, maybe you should tell your story.’ She didn’t want to – she never did. Finally I said, ‘if you tell your story, it might help somebody else.’”

Ida Linehan-Young is a best selling author of four novels of historical fiction, and now two personal non-fiction books about her life’s experiences.

In 2014, she brought forth No Turning Back: Surviving the Linehan Family Tragedy, which was her own account of surviving the fire and growing into adulthood. She tried to mirror the stoicism of her mother until the emotional and psychological pain could not be set aside any longer and the book became an account of Linehan-Young’s resilience.

Talking about it

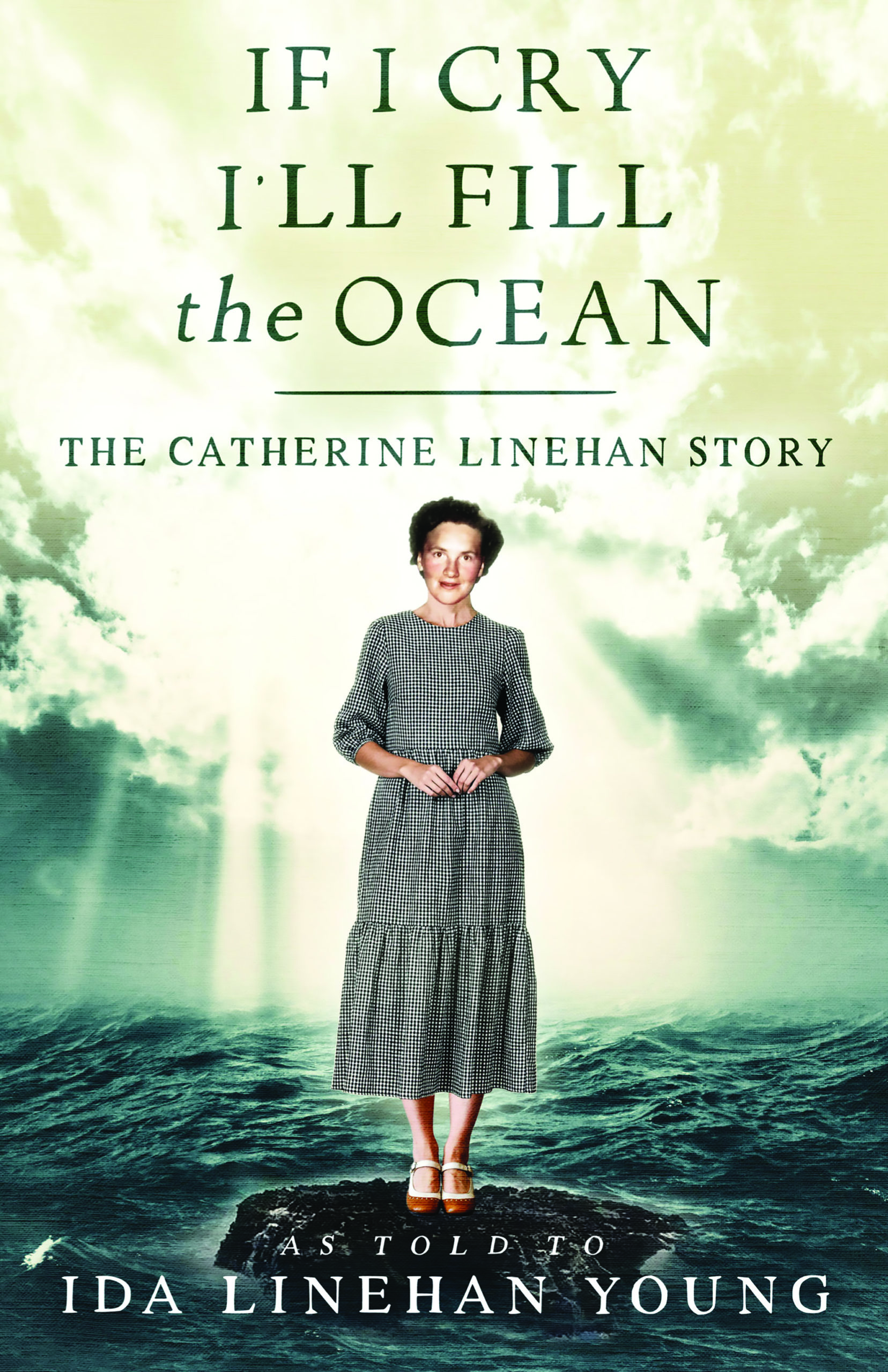

Now comes the follow-up, If I Cry, I’ll Fill the Ocean, a common response from her mother, Catherine, when asked why she didn’t open up about the emotions in her life.

In starting the book, Linehan-Young’s approach had to be gentle.

“She finally started to talk about the fire and I said, ‘Ok, I’m going to interview you.’ We would sit down in the kitchen over three days and she’d answer questions. We were very clinical about it, we didn’t have any aspirations that we were going to sit down with the two of us wanting to cry. Nothing like that.

“When I wrote my book, I disconnected and wrote it as if I was writing Mom as a character. But that was hard. For example, I had to ‘kill off’ my father. He died 20 years ago but it took me three weeks to write just that little piece, a couple of pages.”

She now explains away her mother’s lack of emotion as a product of the times in which Catherine grew up. The suppression of emotion and thought was a cloaking device, a way to cope. “It was a time when nobody talked about it,” Linehan-Young says of the period and how her mother’s generation dealt with grief. “After my first book came out, people in the community read it and everybody had to cry, or had an epiphany. That was the one thing they said, ‘nobody talked about it.’

“It was the only thing [Cathrine] could do. She didn’t know anything else to do. There were times when somebody would die and the men didn’t cry, but the woman cried at the coffin. And then, that was it. Women, especially bearing children, just kept going because they had to.”

Ida had burns from the fire and ended up being in hospital and requiring surgeries, which in turn placed her mother under more stress.

“She thought I was dying and she wanted to be strong for me. By the time I got home from one hospital stay, I had to go back for more. So there was never a time for her.”

If I Cry, I’ll Fill the Ocean was written while Ida and her family, like everyone, have been dealing with the pandemic and various lockdowns. Even as the author gets ready to greet people for a book launch on May 1 in North Harbour, her mother has been on lockdown in a long-term care home, after contracting COVID. The virus spread to her and her family, but Linehan-Young says everyone is now on the mend.

Given the extended periods of family separation, she admits she had to be judicious about what passages of the book she let her mother review.

“I didn’t want her to read about the fire when she was by herself. I wanted to be with her because I didn’t want the book to trigger her, to have her crying and nobody able to get to her.

“I gave her other parts to read, like before the fire, or bits about where I was born, things that wouldn’t be so sad. But as she read it on her own, I talked to her every day and she said, ‘I really liked it. As a matter of fact, I loved it!’ She said it was a really good job. I think, she’s kind of pleased with herself, like maybe she sees herself as a character.”

What mom went through

As Linehan-Young gets ready to meet readers at book launches, she’s considering the generational aspect of what her mother went through, what she as a daughter has lived through, and the world where her own daughters live. The expectations of life for a woman has changed so much down the years.

“Young people today are probably living a dream, everything is at your fingertips. Go online to get the latest iPhone or something. I wanted my kids to have the stuff that I didn’t have. But back then, you grew up and you got married and you became whatever a woman became. You became whatever a man became. You didn’t have more plans than what you were at the moment.”

“If you were a woman, you were a wife, and that was it. If you graduated school, you got married and then became a parent. Absolutely nothing wrong with being a parent, but you didn’t have aspirations over that. It was just as much to be a woman as it was to be a cow or a sheep. You’re valued for having children and that was it. Not much beyond.”

However, as this book is set for store shelves, Catherine Linehan will have an impact on readers in ways she might never have dreamed. For her daughter, Ida now gets to draw a curtain on one aspect of her life that she hopes will serve as an inspiration for others to express grief and celebrate the triumphs of a life lived and sustained.

Ida Linehan-Young’s book, “If I Cry, I’ll Fill An Ocean – The Catherine Linehan Story,” will be in the shops from Flanker Press. A book launch in North Harbour is set for Sunday, May 1, 2pm at the Community Hall.