By: Russell Bowers

A small coastal town in British Columbia suffered a powerful loss when The Titanic sank to the bottom of the sea, taking hopes and dreams with it

If anyone from this province happened to find themselves in the coastal city of Prince Rupert in British Columbia, they would no doubt feel at home. “Rupert,” as locals call it, is a place defined by its links to the sea for fishing and recreation. It wears its badge as the 4th rainiest place on the planet with pride.

The city itself is on an island and residents have to take a ferry to the airport located on another nearby island. In fact, quite a few Newfoundlanders have relocated to Prince Rupert and call the place home. This evergreen place of trees and ocean was settled for thousands of years by the Tsimshian people of the coastal mountains. Its harbour was safe and deep, the area rich in natural resources.

When the Europeans started to arrive in the 1820s, they saw potential and trading with local First Nations was robust for several decades. The fishery drove the economy with fish plants and cannery operations dotting the north coast.

Grand Trunk Railway

By 1910, establishment of Prince Rupert as an important western port was well underway. The Grand Trunk Railway preferred the location as it was (and still is) two days closer to China than anywhere else on the western seaboard.

One of the early proponents to make Prince Rupert the preeminent port for the west was Charles Hays. Hays was president of the Grand Trunk Railway and under his leadership, the railway opened and developed many western towns across the turn of the 20th century.

He envisioned Rupert as a “made-to-order” town, elegantly planned and ready for an influx of new residents. Hays aggressively forged ahead with plans to build a second railway in Canada connecting Winnipeg to Prince Rupert. He lobbied the Canadian government for subsidies, relentlessly courted bankers and financiers in New York and London to get on board with his grand dream. He even had plans drawn up to build a twin hotel of the Empress, the iconic building in BC’s capital of Victoria.

As the project gained steam, it also lost momentum. Workers demanded wages equivalent to their American counterparts, and supplies chains were getting harder to maintain and more expensive. Hays himself was relentless in demanding the highest standards as he had boundless confidence he could raise whatever capital was necessary to see his plan through.

In the spring of 1912, Hays travelled to London, England, to once again sell his vision. Cabinet members in Ottawa were growing weary of his demands, so finding new sources of capital was key to completing the route to the north coast. While in London he received word that his daughter, Louise, was having a difficult pregnancy. He was also keen to return as he also had an invite to the gala opening of the Chateau Laurier, scheduled for April 25.

Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, invited Hays to join him on a transatlantic crossing to discuss business. Hays was initially reluctant, as he ironically objected to the rapid expansion by steamship lines to win passengers with ever-faster vessels.

Hays is reported to have said, “The time will come when this trend will be checked by some appalling disaster.”

Whether or not that is true may never be confirmed as Hays boarded the new vessel, RMS Titanic on April 11, 1912. Hays brought along his wife, Clara, another daughter and son-in-law, his personal secretary and a maid. They all shared a deluxe suite on the Bridge Deck.

When disaster struck just before midnight on the evening of April 14, Hays escorted his wife, daughter and maid into a lifeboat. Hays, his son-in-law, and secretary all remained behind and perished at sea.

Even though Charles Hays was celebrated as one of North America’s greatest railwaymen, just a few years later, his plans for a great western port at Prince Rupert also met their demise. The GTR tried to carry on with his policies but Hays had deceived investors with guarantees he did not have. The government of Canada seized Grand Trunk assets and the focus of railway building shifted away from northern British Columbia.

The good old days

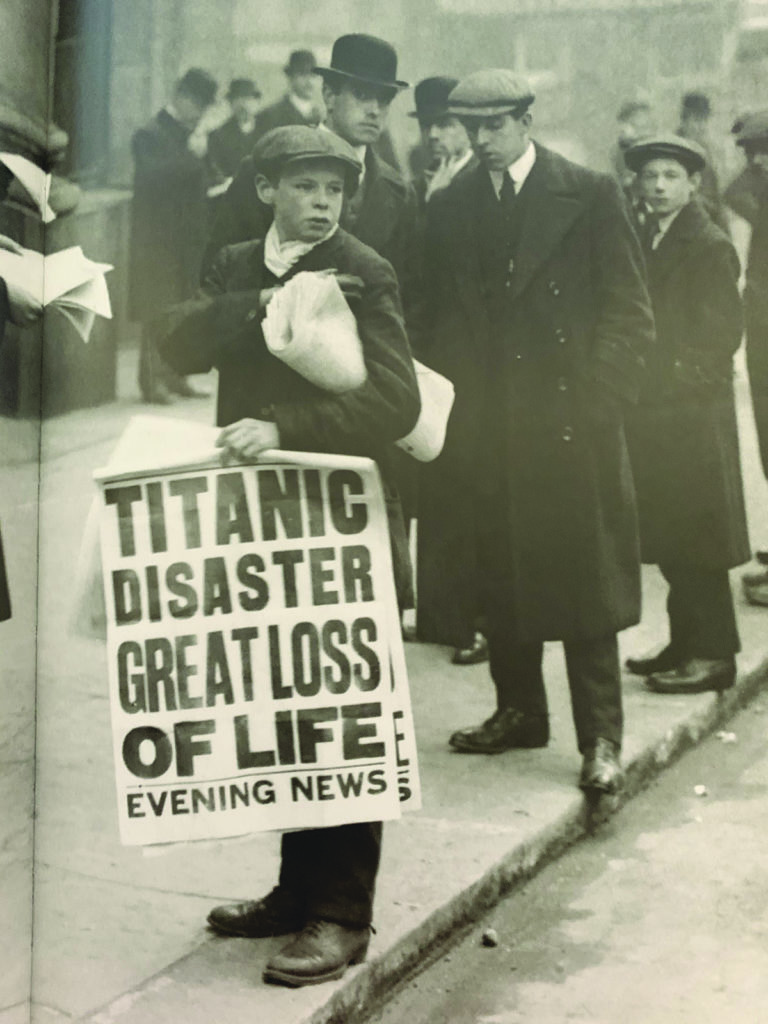

The Titanic disaster has always had a special place for many who live near the Atlantic. The ship’s potential has consumed many in much the same way that Hays himself was consumed by his dream. But for one community nestled in a coastal rain forest, The Titanic still casts a shadow. In 1964, journalist Allan Fotheringham wrote, “In Prince Rupert, they still talk of the sinking of the Titanic as if it was a local shipwreck.”

Prince Rupert is the stuff of dreams that almost were. A place where people still talk of the good old days of the fishing industry. Fishermen and captains would roll into local bars and shops with fistfuls of hundred dollar bills. A modern port for the 21st century starting construction but 20 years on, the city still struggles to get itself on the global shipping map. Cruise ship visits aren’t as frequent, out-migration is still a problem, and many point to closed businesses and lament what “used to be there.”

Up and down the coast of BC, the landscape is dotted with communities that “used to be there.” You see a few remnants of the vibrant places that once bustled with a busy trade in salmon. As business dried up, residents simply moved on. Like the bones of a sunken ship, the bones of houses and wharves lay in wait for nature to reclaim.

However, Prince Rupert perseveres. It still peaks out of the rain, drizzle and fog to proclaim, “we are still here.”

You can always spot the tourist in Prince Rupert because they are the ones carrying an umbrella. If the weather isn’t, you can count on locals to be eternally sunny. One day, their ship will come in. Even it wasn’t to be The Titanic.